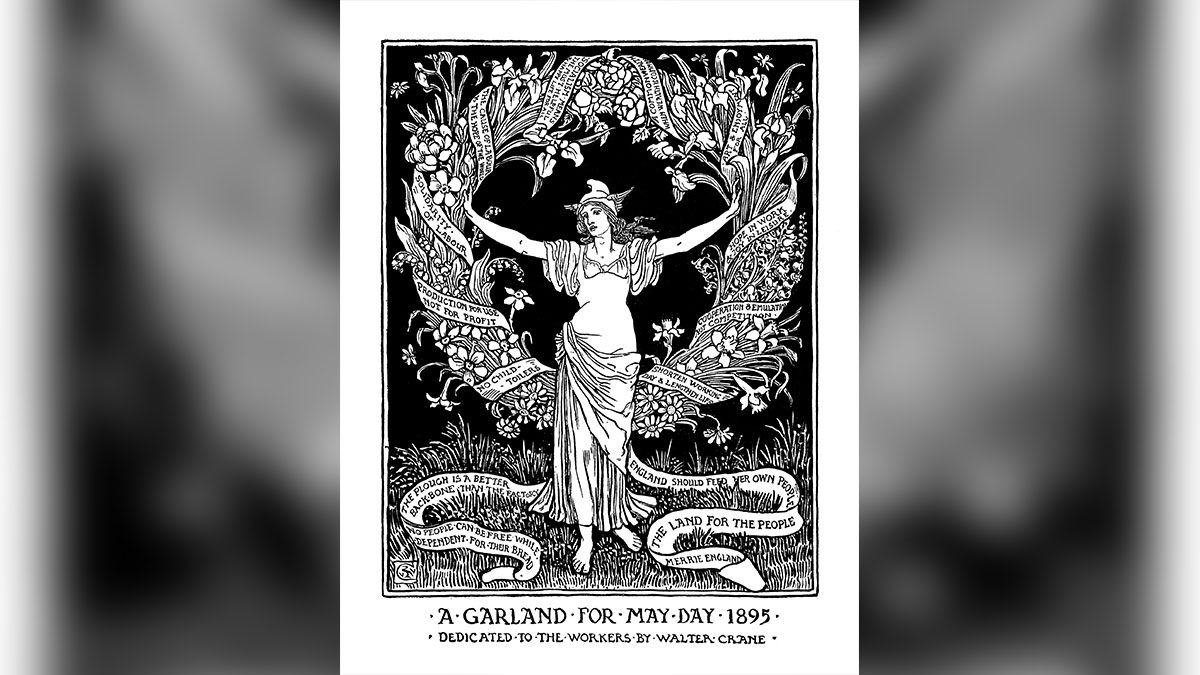

Dancing round the Maypole on the First of May is an ancient custom. Only in 1891, however, did May Day become an occasion for workers’ demonstrations. The date was chosen to commemorate a police massacre during a rally at Haymarket Square in Chicago on May 4, 1886. The rally was in support of a strike for an eight-hour working day, and the eight-hour day became one of the two main demands raised in May Day demonstrations, the other being world peace.

The struggle for world peace got off to a promising start when in August 1904, in the middle of war between Japan and Russia, leading Japanese and Russian socialists Sen Katayama and Georgi Plekhanov shook hands on the platform of the Sixth Congress of the Second International in Amsterdam. But a mere ten years later, in 1914, the main European socialist parties collaborated with ‘their’ governments in unleashing the dogs of war. The fratricidal slaughter that came to be known as the Great War and then as World War One.

The struggle for world peace is altogether too depressing a subject. An article in celebration of May Day should have an upbeat tone. Let’s concentrate on the demand for the eight-hour day.

Dark Satanic Mills

It appears that the demand for an eight-hour day was first raised in 1817 by pioneer socialist Robert Owen. This was at a time when 14 or even 16-hour days were imposed on adults and young children alike in the factories of Britain’s industrial revolution – ‘these dark Satanic Mills’ as William Blake called them in his poem Jerusalem.

Over 200 years have passed since then – surely time enough for us to push working time down to eight hours a day. Or down even further. So you might have thought.

And workers have achieved that goal. In Europe. Especially in Germany, where in 1978 workers staged a six-week national strike for a 35-hour week. The strike failed, but a 37.5-hour week, i.e., a seven-and-a-half-hour day, did become standard. Last year Germany’s largest trade union, IG Metall, won a 28-hourworking week for 900,000 workers in the metals and electrical industries. How about that?

Not in the United States

But not in the United States, even though American labor movement publications called for an eight-hour day as early as 1836.

True, some groups of American workers did achieve an eight-hour day quite early on. In 1868 Congress passed a law establishing an eight-hour day for laborers and mechanics employed by the federal government (at the same time their wages were cut by 20%). The 1870s saw the rise of Eight-Hour Leagues. A big strike in New York City won the eight-hour day in 1872, mostly for building workers. By 1905 the eight-hour day was also common among printers.

But most American workers were still working at least twelve hours a day.

The eight-hour day spread more widely during World War One, when labor was in short supply. In 1914 the Ford Motor Company shortened shifts from nine hours to eight, and after some time other companies in the automobile industry followed suit. The Adamson Act of 1916 established an eight-hour day for railway workers.

The Fair Labor Standards Act, enacted under the New Deal of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1938, did not establish a maximum working day or week, but it did create an incentive for employers to limit working time. It did this by means of the rule that employees working over forty hours a week must be paid at an overtime rate 50% higher than the standard rate.

Gradual improvement continued in the 1940s. Working time stabilized in the 1950s and 1960s at an average level of about 42 hours a week. American workers were fairly close to the eight-hour day at that time, but most never quite reached it.

And since the 1970s average working time has increased again.

At present 86% of male workers and 67% of female workers have a working day longer than eight hours. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average American works 8.8 hours a day. A 2014 national Gallup poll found that respondents worked on average 47 hours a week, i.e., 9.4 hours a day. Many reported working at least 50-hour weeks, i.e., 10-hour days.

Two Full-time Jobs

Moreover, overtime is not the only factor that needs to be taken into account. Over a third of American workers (37%) have second jobs. Many are working two full-time jobs, that is, 16 hours a day – just as workers did in Britain in the early 19thcentury. There’s progress for you!

The picture looks even worse when we shift our attention from the individual worker to the family or household. In 1960, only 20% of mothers worked. Today 70% of American children are ‘latchkey kids’ who live in households where all the adults are employed.

Over 200 years since Robert Owen first set the goal of an eight-hour day and it’s still out of reach! And this despite the huge rise that has taken place in the productivity of labor!

As I said, an article in celebration of May Day should have an upbeat tone. That is why I decided not to discuss the prospects for world peace. But I fear that I have still not achieved the optimistic note that I was aiming at. If so, I sincerely apologize.

It is customary to end an article by explaining the conclusions to be drawn. Instead I invite you to choose among the following:

- Emigrate to Germany

- Do not read any more articles by this author

- Work for socialism

- Organize more, bigger, and better May Day demonstrations

- Study the experience of European trade unions